To create services that are effective, we try to use the language our users do. It’s essential if we want people to understand and trust what we’re saying.

But, this may not be the same ‘official’ language we use in government.

Julie Aberdein and I are content designers working with the team who research, design and build the health-related questions for Universal Credit. As with many services, coronavirus (COVID-19) forced us to review how we get this information from people – they could no longer bring documents to our offices. We needed to change the process, and in doing so, we reviewed how we were asking people about their health.

By researching the journey claimants go through, we learnt that we could be doing more to help people understand what we were asking. And one way we could do this was to use the language they do.

Asking about people’s health

Universal Credit helps people with their living costs. You may be able to get it if you’re on a low income, out of work or cannot work.

To make sure we offer people the right support, we ask whether their health affects their ability to work or look for work. If it does, we ask if they have a fit note from their doctor.

A fit note is a written statement from a doctor giving their medical opinion on someone’s fitness for work. Fit notes replaced sick notes in 2010.

Despite being in circulation for 10 years, we learnt that the term ‘fit note’ can still cause confusion and uncertainty for claimants.

Why government replaced ‘sick notes’ with ‘fit notes’

Fit notes replaced sick notes in an attempt to fundamentally change the perception and recording of sickness absence.

In 2008, the 'Working for a healthier tomorrow' report urged the government to review the use of sick notes, believing that they were too restrictive.

The report suggested focusing instead on what people can do rather than what they cannot – on their fitness for work. And so fit notes were born. Allowing doctors to say what work their patients can do, as well as what they cannot.

Replacing sick notes with fit notes marked a shift towards a more collaborative and aspirational approach to work and health.

But a shift in people’s thinking takes longer. And it takes time for new terms to enter our common vocabulary.

What we learnt

Our user researcher, Jamie Englert, spoke to Universal Credit claimants and showed them the questions relating to fit notes.

From research we learnt that the term fit note was not well understood. People had to translate it to the term they would naturally use to be able to understand and answer the question. Some of the comments from the research showed that ‘fit note’ was causing confusion:

“…I always call it a sick note”

“Sick note, I wouldn’t call it anything else”

“No idea what it [fit note] is – is it a sick note?”

- Claimants in user research

They weren’t alone. Looking at discussions on online forums and social media groups, we saw that ‘sick note’ was still being referred to, and noticeably more than ‘fit note’.

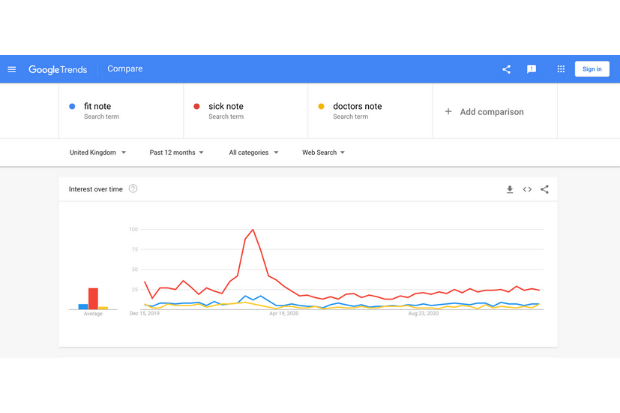

To quantify this, we looked on Google Trends (which shows trends in people's search behaviour within Google and YouTube) and compared terms to see which were more commonly searched.

‘Sick note’ was consistently searched for more than double that of ‘fit note’ or ‘doctors note’.

Between 22 and 28 March 2020, at the start of the first lockdown and when lots of people were ill with coronavirus (COVID-19), it was searched for almost 8 times more.

We learnt that by using the ‘official’ term that government wants people to use, we were not using the natural language of our users. We were instead forcing people to spend longer than necessary working out what we were asking, increasing uncertainty and risking people misinterpreting the question and answering incorrectly.

We had the evidence to make a change

Content design is evidence-based. We use research and data to design the most effective way to get information to people.

By doing this research and analysis, we had the evidence to convince people within government that using the language our users do helps:

- claimants understand what we’re asking

- government get accurate information

So, we updated the question to acknowledge that people may also know ‘fit note’ as ‘sick note’.

We want to design questions so that they get the information government needs without increasing the mental effort of the user. We’ll monitor the impact of this change to see whether, as we hope, it means that:

- more people can answer this question

- they can answer it quicker

- they’re more confident that they're giving government accurate information

User centred language across all services

It’s easy to become so familiar with a process or service that our objectivity is compromised. People often use the language they’re most familiar with, without realising that these terms are unknown to the users of the service.

But terms that make sense within an organisation, business or team may not to people outside that group. To create services that people can find, use and trust we must use language that’s meaningful, relatable and understandable.

Government services help a diverse range of people with varying needs. Using unfamiliar terms that are ambiguous can mean the difference between giving the right or wrong information.

Using ‘sick note’ is one small example. But content designers in government research and reflect the users’ language across all the services we work on.

We use plain English, remove jargon and use terms that we know are familiar. We focus on language that can be understood and is meaningful to the people who interact with us. As Claire Parry said in her recent blog post 'How content design helped us improve the Universal Credit experience':

“When it came to the content, it was really important to adapt DWP’s language for the claimant. I did not want to force them to work any harder than they needed to. For example, internally we use the word ‘deduction’ but from the research we know claimants use the language ‘money taken off’.

Find out who to contact about money taken off your Universal Credit is now a simple and easy to use service that only ever takes a person to the place they need to be.”

And Jane McFadyen writes about how we changed the name of ‘Check your state pension’ to ‘State pension forecast’ to reflect the language we knew people use, reduce confusion and improve a live pension service.

Using the language our users do removes doubt. It helps to make government services more trustworthy, quicker to find and easier to understand for the people they support.

Services Week is an annual event showcasing the best in service transformation across government. For more information on Services Week 2021, take a look at the Services in Government blog.

1 comment

Comment by Rajitha Ratnam posted on

Super interesting!

Even after 2010 I still had doctors who told me off for calling it a fit note - so perhaps if the doctors themselves used the right language people would be more likely to use that phrase?