As user researchers, our job is to understand the needs and behaviours of users so that we can help our teams deliver better services. The most obvious and best way to do this is to speak to users directly. But sometimes, it isn’t always possible or ethically responsible for us to do this.

This could be because:

- users can’t take part in research due to health conditions or other circumstances

- we’re researching topics that may remind users of past trauma

- users are unable to take part in the entirety of the research

So what do we do if we can’t speak to users?

We use proxy users. Proxy users are people who are not your actual users, but who are close enough to have a very good understanding of the user. They include people like support workers, physicians or charitable organisations.

At a government design community meet-up in early January 2019, researcher Sam Groves from the Ministry of Justice spoke about the importance of conducting user research withproxy users when researching sensitive topics.

How have we used proxy users?

We recently conducted two projects with proxy users. In the first, we worked with proxy users when testing phrases to explore how our users might understand the term “terminal illness”. We made a distinction between using ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ proxy users to understand the end users’ potential challenges.

We defined primary proxy users as someone who has frequent interactions with the actual user. For this project it was support workers, health advisors and charities.

Secondary proxy users are usually subject matter experts who don’t necessarily have frequent interactions with the users but have a strong understanding of the context. In this case, our internal policy and operations colleagues became our secondary proxy users and helped us to sketch out an early version of the prototype based on their existing knowledge.

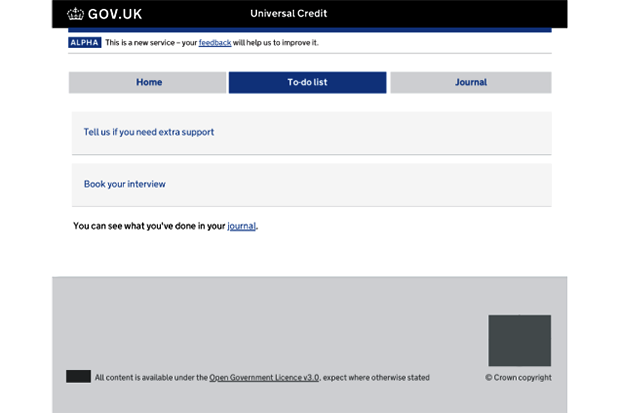

In the second project, we spoke to support workers of domestic violence victims when testing a way for our users to tell us about extra support that they might need when claiming Universal Credit.

By speaking to support workers first, we were able to explore language in the prototypes that might trigger difficult feelings or memories for users, as well as anything else that might encourage or discourage these users from telling us about the help they might need.

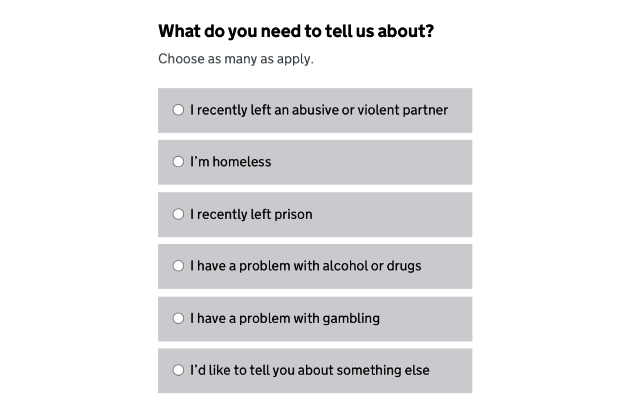

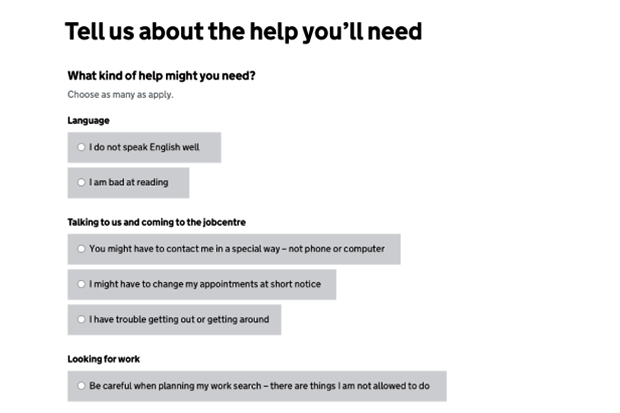

We showed the support workers two prototypes. The first asked our intended users to tell us about the problems they face. The second, based on Scope’s social model of disability, described the ways in which our service can address them.

For example, in prototype 1 we say: “I’ve recently left an abusive or violent partner”; whereas in prototype 2 we say: “You might have to contact me in a special way, not phone or computer”.

For example, in prototype 1 we say: “I’ve recently left an abusive or violent partner”; whereas in prototype 2 we say: “You might have to contact me in a special way, not phone or computer”.

As expected, the support workers preferred the second prototype. It shifted focus toward how to deal with these situations in a constructive way and reflected the way in which support workers are trained to speak to survivors of domestic abuse.

Having spoken to proxy users first, we were able to test future prototypes with confidence and with language that was sensitive to the conditions and circumstances of our intended users.

What did we learn from this approach?

We saw several benefits from researching with proxy users:

- reducing unnecessary interactions with users

- engaging proxy users early helped us narrow our options and bring the design to a stage where we felt we could get feedback from actual users

- we didn’t have to expose actual users to sensitive topics repeatedly

Although proxy users can be a valuable source of information, they will never replace actual users. Here are some reasons why:

- proxy users might view actual users from their own perspective and biases

- getting a deeper understanding by talking to users can drastically change the way we design something. By only speaking to proxy users we will just scratch the surface and deliver designs that don’t meet the underlying needs of users

What to consider when researching with proxy users

If you are thinking about doing research with proxy users, use a combination of proxy and actual users. In the example we gave above about our work at DWP, using proxy users was very useful for us, as a first step. Finding actual users and establishing a relationship is the next step towards getting more real-life feedback.

Use your research to confirm proxy user’s perceived concerns and fears about real users (aka potential biases). You can treat these concerns as hypothesis and test with your actual users where possible.

You should also involve primary proxy users in your research sessions with actual users. They are often trusted by actual users and can help users feel more comfortable and open during research sessions.

Like this blog? Why not subscribe for more blogs like this? Sign up for email updates whenever new content is posted!

If you’d like more information on our experience working with proxy users, or if you have experience to share, leave a comment below!