My name is Simon and I’m the user researcher on the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) Digital project. It’s my job to make sure the team is fully aware and appreciative of who our users are.

As Leisa Reichelt wrote recently:

“You are not your user and you cannot think like a user unless you're meeting users regularly”

Our users aren’t ‘just’ statistics either:

- They aren’t ‘just’ one of several 100,000 PIP claimants

- They aren’t ‘just’ one of the 11 million people in the UK with a long term health condition or disability

- They aren’t ‘just’ in a family where 21% of children in families with at least one disabled member are in poverty.

Meeting user needs during user testing

When we’re designing services that meet the needs of DWP’s customers, we meet our users regularly. For PIP, we take extra steps to give our users the right level of support when we invite them to test our services. Our users may need to bring a carer or family member; they might need to take breaks during a user testing session; our users might need to test the service with assistive software or on their own devices; and they may prefer us to work with charities who are already supporting them, or for us to visit them in their own home – we’re able to meet all these needs.

When we’re designing services that meet the needs of DWP’s customers, we meet our users regularly. For PIP, we take extra steps to give our users the right level of support when we invite them to test our services. Our users may need to bring a carer or family member; they might need to take breaks during a user testing session; our users might need to test the service with assistive software or on their own devices; and they may prefer us to work with charities who are already supporting them, or for us to visit them in their own home – we’re able to meet all these needs.

Understanding our users’ lives

Our users are real people, with real lives, families, friends and goals. They are John. I met John and his daughter recently at a user research session. John gave me permission to tell his story and when he saw this blog he said “I’m amazed at how well you’ve captured my story”.

John is 59 and a father and grandfather. John used to be a goalkeeper in a football league club in his youth. In one game, John saved two penalties for the youth team. The opposition striker wasn’t best pleased and kicked him in the back, bursting two of his vertebrae. This ended his chance to be a professional footballer, and also made it difficult to pursue his second career choice, as a joiner, so he set up a successful business. The injury resulted in the degeneration of his nerves, and he knew it would deteriorate throughout his life. The rheumatoid arthritis he developed in his teens didn’t help.

In the last few years this has prevented John from working, he had to sell the business he spent over 20 years building and that he loved being a part of. Selling his business meant he lost the lifestyle he took for granted - John had to get rid of his car, downsize his house and stop taking the holidays that meant so much to him and his wife.

This affected his mental health so much he became irritable and aggressive, he’d have “argued with a brick wall”. After his heart attack John realised he needed to get help and was referred to a psychiatrist, who helped a great deal.

John was too proud to apply for Disability Living Allowance (DLA). He was having difficulty coming to terms with the fact that he could no longer do a job he loved and that applying for DLA would be like "admitting and accepting his condition". His wife and his daughter had to apply for him.

He’s now concerned that because he loses the feeling in his hands he can’t be sure he isn’t gripping his grandson’s hand too tightly or not tightly enough. John worries that he’ll hurt his grandson, or not hold him tightly enough when they’re walking near the road.

To quote Leisa again: “needs can be functional things people need to do, for example, to check eligibility. Needs can also be emotional, perhaps people are stressed and anxious and they need reassurance.”.

Designing services to meet users’ needs

We can use John’s story to design a better service. We can find out what he needs to do and then try our best to get out of his way. We can make sure our designers and developers are building a service that John can use. We can work to ensure the language and tone support and reassure John and that the questions we are asking him are clear and transparent.

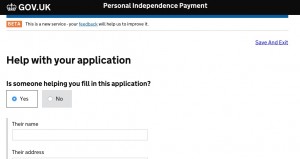

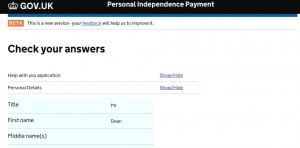

We know from research that when people are completing an application for PIP they can get tired, or they need to take a break to take some medicine, or they lose concentration. People also want to ‘sleep on it’, they have a first go at their answers then rework them over several days. And they really want to keep a copy of what they’ve sent us. Knowing this, we can design a service that considers this and allows people to save their application

We’ll continue to meet our users regularly as we design the PIP digital service. We share our findings with people involved in delivering the service too, to help them to understand John’s life and how we need to design a service that helps John and all users to get to their goal quickly and easily.

13 comments

Comment by Gary McFarlane (www.assist-Mi.com) posted on

Extremely interesting insight to how DwP are addressing users access needs. We are all different uses with different needs and as DWP undertakes transformation and embraces technology. Customers like John also go through life changing transformation and ensuring access and any barriers are addressed and removed just as Simon has highlighted. Great insight to the user testing and this show how serious Simon and his team take accessibility and user ability ensure Government DWP service are design online services to meet the customers needs. Excellent

Comment by Simon posted on

Hi Gary, thank you for this. We're working really hard to ensure the service is not just accessible but usable and frustration free for users as best we can. This involves using lots of different groups and charities who can help us get out there and meet people.

For example, I was testing with users at Sense (the charity for people who are deaf blind) last week.

Comment by Claudio posted on

Great blog Simon! I think the point about tone of government communications, of our 'face' to our target groups is essential. People tell us they feel it is often cold, jargon-filled, uninviting. Add a general lack of trust and barriers to applying like this user's own mental battles and we're just keeping barriers. It's a government-wide issue and the more we can discuss and share good practice the better. To achieve a tone that is sympathetic, helpful, clear and unsuspicious. Keep it going!

Comment by Colin Coote posted on

Be interesting how you go about a person of 64 pushing 65 Totally Deaf & Poor Balance Problem & severe Tinnitus because being Totally Deaf is very hard to deal with, who has gates up in bed because of falling out, a guy who can't drive anymore his wife does it, he uses Scooter and he finds that a nightmare because of state of Pavements that jog head so he has to go slow slow, who now use noise squeaker to alert wife at night, to go to loo etc.

I just wondered how you understand Deafness or Deal with it, What is Totally Deaf, what is Profoundly deaf, severe,hard of Hearing.

It would be interesting.

Be honest do you think That Totally a Deaf is same as Profoundly Deaf.

Because I wonder how you Deal with Deafness or define.

Comment by Simon posted on

Thanks for taking the time to respond. The PIP service doesn’t define a person by their condition, or the name of their condition, instead we want to understand the impact a condition has upon their daily life. So the person in your example would be able to report the difficulty they have communicating with people because of their hearing loss and tinnitus. They would give information about balance issues in the section about moving around.

I’ve done testing with people who are deaf before and was testing with people who were deaf and blind just last week. We checked beforehand what their communications needs would be. Generally the advice we received was to speak more clearly and slightly louder for most of the people. We knew this wasn’t appropriate for one person so we organised a hands-on BSL user to help us to communicate with each other. We made sure the computer was set up for everyone to use, this included having a screen reader for some people and magnification software for others.

The more research we do with users who are deaf, the more we will be able to understand the impact of their condition. We know that this will help us build a better digital service.

Comment by Andrew Arthur posted on

PIP discriminates against deaf people because :

1. There is nowhere on the PIP application form where deaf people can describe their affliction. When you consider that deafness is a complicated sensory disability with many social side-effects one wonders why this is?

In fact deaf people have to make their application on separate sheets of paper in which they describe their problems and provide evidence from a professional. Deaf people who don't have the ability to write essays are excluded from this. There are no explanatory notes.

Discrimination.

2. When the physical examination comes round, deaf people are discriminated against. This is because the examiner is allowed to use an empirical test for hearing loss. Despite the fact that applicants will have supplied full details as above I have seen evidence that deaf people are being subjected to an aural test in the examiner's office. This test consists of the examiner speaking across a room behind the deaf person's back. They are then judged on their response to this.

My question : Why is this being done? The deaf person will already have supplied ample evidence from medical professionals as to the extent of their hearing loss. Why therefore are they subjected to a further test using methods that became outdated after WW1?

Discrimination. And also lack of common sense. With scientific evidence available why is this old fashioned test available?

Finally here is evidence of the difficulties that deaf people are having with PIP.

http://www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/community/forums/deafness-and-hearing-loss.aspx?g=posts&t=10978

Comment by Simon posted on

Thanks for taking the time to respond. One of the reasons I wrote the blog was to get feedback from people, it’s the only way we can learn how to design and build better services. Overall these issues are exactly why we do user research - to understand the difficulties people have with making a claim for PIP so that we can design a service that meets users’ needs.

One aspect of PIP that we’re working on and changing is the language we use. This should result in questions that are easier for people to understand. I’d agree that one of the difficulties we saw in earlier versions of our design was that it was difficult for people to realise what information they should provide and how to answer certain questions. Recent testing and changes we’ve made to the digital PIP claim have improved this. We’ve tested with people who are deaf and hearing-impaired, people who are blind and also people who are deaf and blind. We’re continuing to update the design based on their feedback.

We’ll be researching whether people who are deaf are able to tell us about the difficulties they have in the sections about communicating and mixing with people. Given that many deaf people also have balance issues we’ll test if this information is presented in sections on moving. One thing we’ve learned during testing is that people need a chance to add something we may have not asked about. The digital service will allow people to do this.

Comment by Lynne Almond posted on

Hi Simon

Have you looked into the language you use to describe a person who accesses your form. I personally take objection to be called a user . Have you checked the definition of the word you would have found that yes it does define as someone who uses a computer to access a service but it also defines as someone who is a drug user and someone who exploits another person. Person I find the term user is in bad taste to say the least. Why can we not be called a PERSON who accesses your service. Calling someone a user comes across as Impersonal and disassociative not inclusive and certainly not friendly.

Comment by Simon Hurst posted on

Hi Lynne, thank you for taking the time to comment.

We use the term 'user' when we are building Government services in line with the design approach commonly called 'user centred design'. This means that we place the user at the heart of everything we do when designing our online services. We build the service based on what the user needs from that service, not what government believes the user needs.

Personally I like to use the person's name wherever I can, so throughout the blog I refer to the individual person as 'John'. This is how, as a user researcher, I feed back my findings to the team. So when I update the team about my testing on Monday I'll talk about the needs of Annabel, Malcolm and Annette.

Comment by Lynne Almond posted on

Thank you for clarifying your position. It is all too common when dealing with various agency's that we are not treated with dignity and respect as a person. I do feel in your comments that you are mindful of this.

I believe this is why people are frightened and wary about filling in your assessment forms as previous experiences in dealing with the actual assessment people is vastly different. Almost coming from the opposite mind set. Rather than making it easy and comfortable to find out about your needs, it seems to be geared up to to a defensive position where they try to actively find reasons to mark you down wherever they can find the smallest of reasons. Eg you've got a hearing aid so your not deaf and can communicate. When this is not the case, emphasis on AID.

Thanks again for your reply

Comment by Ric Walsh posted on

A sterling effort Simon, and an informative blog. Glad I got to hear you recount the John story face to face - understanding the issues people are facing helps drive the 'user' centric vision.

Comment by Mike Hughes posted on

Several key aspects of this get missed repeatedly.

1) Going to charities in order to access users does not give any kind of representation of user needs. Most disabled people have at least some frustration with the charities that fund raise; raise awareness; fund research or represent their views. Most users put forward by charities are those who are vocal, articulate and regular participators. That is not a representative perspective on the consequences of disability. I regularly attend consultation events where, for example, users put forward by the RNIB are the same people repeatedly and their perspective is essentially their own blind or mostly blind rather than articulating the wider experience. Views put forward, and I don't confine this to the one charity at all, are often wholly unrepresentative.

It's a bit like having a "Disability Qualified Tribunal Member" on a social security appeal tribunal panel. Recruits fall almost exclusively into ambulant, middle class, former workers with a perspective towards disability biased wholly toward "well if I can do this what on earth prevents you from doing so!". It's neither helpful or accurate.

Far better to look for lived experience from user groups working in other contexts e.g. the DDRG group funded by TfGM in Greater Manchester, who look at Metrolink accessibility.

2) Making a form accessible at the outset of the claim process is one tiny part of the process. In the case of PIP there are huge problems with everything around the form but those things are mysteriously excluded from accessibility conversations because it's too difficult to get into. Some examples? Of course...

- the leaflets advising that DLA is ending are shockingly bad.

- communication with the hearing impaired community has been so far that many have completely messed up their DLA entitlement because their limited understanding of official communications led them to believe PIP was an addition to, rather than a replacement for, DLA.

- the odd video for people with a hearing impairment or a learning disability is meaningless. The entire process needs videos else something inevitably goes wrong.

- the letters inviting people to claim PIP are too long; have been subject to much ministerial interference (which paragraph goes where) and are an inaccessible, incomprehensible mess. They are wholly inappropriate for any sensory impairment; mental ill health and learning disability as well as anyone on significant amounts of medication which impair cognition; concentration and so on.

- the PIP claim form makes no reference to regulations 4 and 7. The consistent line that this is not necessary is belied by the numbers of plainly, woefully incorrect decision making based on those forms. Make the form as "accessible" as you like but if it doesn't ask the right questions in the first place then you won't be getting the right answers no matter who you talk to.

- the PIPAS software is simply not fit for purpose. It also fails to address regs 4 and 7 but also leads the assessor down illegal paths. So, for example, the legislation allows a claimant to satisfy more than 1 activity under a descriptor. The PIPAS software uses radio buttons that explicitly prohibit the selection of more than 1.

- the obsession with getting people to "tell their story" really doesn't cut to the core of what is required.

3) The above leads to a tick box approach and a concentration on the wrong aspects of accessibility. Making a form accessible to screen readers, good as that is, for example caters for an incredibly small number of the VI community. The majority of people with a VI are sight impaired and not severely sight impaired. Striving to comply with web standards for accessibility is also a red herring. It's perfectly possible to comply with all such standards and still produce a site and form that is utterly inaccessible. The obvious is not missed. For example, have you tested with browsers where users don't use specialist aids such as screen readers but tweak default settings such as magnification. You'd be surprised what happens to the text. Mostly it starts to overlap and become unreadable. Few people even spot it. Ditto changing contrast on a site. It's assumed that some kind of variation on the Windows high contrast accessibility changes is what's needed and yet for the majority of people with a VI what's needed is the ability to switch to a font of their choice and often a background of their choice.

4) The concentration of digital accessibility tends to pretend that people needing to use paper claim packs is the exception rather than the rule. With many disabilities that is simply not true. What work is being done to ensure that the paper pack is more accessible than it currently is?

5) Many people need an advocate or representative to complete their form. How will this work with that scenario?

I would welcome your thoughts on all of the above.

Comment by Simon Hurst posted on

First off thanks for your comments, they are extremely comprehensive so if nothing else at least I know people are reading it!

1) I agree with you on this and it is something we are always aware of. We always bear this in mind when working with organisations who find us people. I'm confident this has hardly ever (if ever) been an issue for us. We do recruit people in a variety of ways. Frequently this is done by a recruitment agency, in a similar way to market research. This means we speak to a wider selection of people, of which having a certain disability or health condition is just one part of their life. The vast majority of these people have never been near a charity or support organisation in their life. They are recruited through online panels, medical recruitment roots or even from off the street. This variety is important to make sure we don't just speak to 'online savvy' or market research savvy participants. We also visit people. We also work with many local or grass root organisations and Disabled People's User Led Organisations (DPULOs) to find people - I've never witnessed obvious 'selection' of people with these.

2) The research I do is admittedly more focussed on the online channel of PIP, however, I am aware of most of the issues you raise. For example, I know from research that English is a second language for people who are deaf from birth. This currently makes it difficult for people to make the initial part of the claim. This then makes it very hard to understand the language used in written communication in general. We place huge focus on making the questions as understandable as we possibly can, however, we recognise that this doesn't make it usable for British Sign Language (BSL) reliant people for example.

The 'tell my story' insight was a strong finding in the early days of research of PIP (well before my time). People felt it was important to be treated as an individual and to be able to describe how their condition affects their life. During research though people often struggle with what to tell us. I've written a blog about this and how we tried to tackle it that should be live here soon.

As I'm sure you can appreciate I'm not able to comment on legislative or ministerial aspects of PIP. I do know that the research we do is shared with other teams.

With regard to regs 4 and 7, this is something we are ensuring we focus on more. We have tried various ways to gather the information on how often the person applying has difficulties on an individual activity basis, the most successful design is now in the digital service. With regard to 'safely, reliably, to an acceptable standard, repeatedly and within a reasonable time period', this is also now in our design and we continue to test other options to ensure the one we have is the most effective.

3) I agree again. One of my pet hates about accessibity is people assume it’s purely about screen readers, which of course it is not. An online channel has the potential to make the process of applying for PIP far more accessible for a wide variety of people if done well. One example of our testing has been to identify that people with learning disabilities have significant difficulty understanding contractions such as 'don't and can't. We have removed any mention of these from the PIP online claim process and are feeding the finding back across DWP and also the gov.uk website. Another example of our research highlighted that the outline of textbox fields of was difficult to see for people who are visually impaired and used a magnifier. When zoomed in we found people often thought there was nothing on the screen. The contrast of the outline was too low (even though it passed the accessibility standard). We not only increased the contrast for PIP but the contrast change is being applied across the whole of gov.uk. Ironically, this was discovered whilst testing with the RNIB. We do test across different browsers and devices, we do change colour contrast and we ensure that people can set their own colours or, if they already have their own style sheet set that we do not interfere with that. I'm not an accessibility tester but I do simple things myself, such as tabbing through the service and making sure it's possible to only access using only the keyboard.

4) Whilst an online service can make things better for many people, obviously this is not always the case and a paper from is more suitable for them. We do share what we learn with the wider programme of work ongoing with PIP.

5) We know this is true. One of the first things we learned is that people more often than not work with someone when completing their form. This may just be a friend or family member and can be for a variety of reasons: helping understanding questions, making sure the answer covers everything they have diffiuclty with, helping to read, helping to use a computer or even just because it makes people feel better having someone with them. We know this makes a difference to the information we get. We know disabled people do not always notice the difficulties they have - it just becomes part of their lives and they miss telling us things. Having someone who knows them makes a difference as they can point out these 'blind spots' and fill in the gaps. In the online service we recommend that people work with them, or take a look over their application before they send it.

We also know people want to be transparent, they want to be honest so we’ve included a screen where they can tell us who helped them if they want to. We tend to recruit pairs for research so that we recreate as closely as possible how people will use the service for real. We are still working on more 'formal' support such as appointees or power of attorneys. We know it's needed and there are challenges like 'is this question about me the appointee or the person who is disabled?’

The other challenge is support organisations - how do we support claims made via them? Again, this is something we are working on. However, the initial focus of the work we've been doing has been making the form and the questions as clear as we can. We know we need to get the best information out of people so we can make the right decision the first time round.